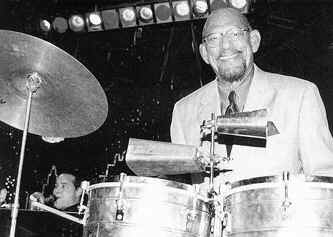

With the recent passing of Tito Puente, Willie Rosario's musical mission takes on a whole new perspective, that of keeping the mambo alive for a whole new generation to enjoy. Willie is ready, willing and able to take on the responsibilty.

Q&A: A Conversation With Willie Rosario

By

George Rivera

Q: Why don't we take it from the beginning, your early musical days?

A: I have always liked music. It's like I was born with rhythm. I was born with timing like they use to say in the old days. When I was just seven years old I would play on tin cans in the balcony of my parents home. When I was about eight or nine years old my mother sent me to music school where I learned to play guitar. When I was about twelve or thirteen I started to study music theory. I was assigned a saxophone. However, I really didn't care for those instruments. When I went into the Army I had to play the bass. Since I knew how to play a little guitar I just applied that knowledge to the bass. When I didn't know the fingering I would fake it. Eventually I became interested in the drums. I came to New York to study with a teacher by the name of Henry Adler, who was teaching Monchito MuŮoz, Papi Pagani, Mike Collazo and Georgie Laguna, a very good drummer who passed away at an early age, and Tommy Lopez, the conguero. He was the one that all the drummers would go to. That is why we all had basically the same style. I also studied with Willie Rodriguez, who was a very famous drummer that lived here in New York. He was a very good reader and studio musician with a busy recording schedule. He was recording on a daily basis be it for television, the movies, radio, or just records. Eventually we would become compadres. He is the godfather of my eldest son. I had the opportunity to play with two or three orchestras in New York. The last one was Johnny Segui's orchestra. When Johnny Segui decided to return to Puerto Rico towards the end of 1957, I decided to form my own orchestra.

Q: Which were the other bands you played with besides Johnny Segui's?

A: Well, one of the bands I played with was that of the tresista, Luis "Lija" Ortiz, who recorded with Panchito Riset. He had his own group as well and it was with that group that I began my professional career. I also worked with Joe Quijano. I was also a member of the orchestra that Aldemaro Romero led here in New York. I played drums with his orchestra, which was the orchestra used for the very first Hispanic television programs on an American network. The shows were aired on channel 9, here in New York. I also played with a few other unknown bands until I landed the gig with Johnny Segui.

Q: What was the experience of starting your own band like?

A: Well, when Johnny Segui decided to return to Puerto Rico I decided to go for it. Since Johnny was returning to Puerto Rico I started recruiting some of the musicians that had been in his band. I then spoke with Tito Puente and Tito Rodriguez, who both contributed music for my orchestra. I would break night every night copying musical charts. The band's first gig was at the Broadway Casino, which was located at W. 146th Street and Broadway. From there it just took off. We would play at a club by the name of El Monte Carlo, which was located at W. 138th Street. From there we landed a gig at the Club CaborojeŮo, which was located at W. 145th Street and Broadway, as the house band. That gig lasted for three years. When that gig was over I recruited Frankie Figueroa, the vocalist. I then recorded our first record for Al Santiago's Alegre label.

Q: Did you use any band as a model for the formation of your own orchestra?

A: Well, we as musicians always have those bands we emulate. I liked the orchestras fronted by Tito Rodriguez and Machito. I learned a lot while I was with Johnny Segui's orchestra. He had a phenomenal orchestra. Johnny's orchestra was the first in New York with four trumpets. He used four trumpets before Machito, Puente or Rodriguez. I liked the sound of those bands and I tried to emulate that sound and swing. I started the orchestra with three trumpets not because that was the sound I wanted, but because of economics. The better the musician the band attracted, the more jobs we would get. I kept that three trumpet format until we started to get enough work to be able to add a fourth trumpet. Afterwards I started looking for a different sound. I didn't exactly know what I was looking for. At first I thought about adding a trombone, but everyone started using trombones. I even thought of maybe using a clarinet with four trumpets! I just couldn't put my finger on the sound I was looking for. One day I went down to the Bluenote where Gerry Mulligan was playing with his quintet. That was around the time that the Bossa Nova was just starting to be heard here in the States. While sitting there in the Bluenote listening to Gerry Mulligan's quintet I hear a passage Gerry plays, along with the bass and piano. It was sort of like a passage we would play in a mambo. It hit me right then and there. That was the sound I was in search of, the baritone sax! I presented the idea to Bobby Valentin, who was playing with my orchestra at the time. Bobby thought it was a different approach for the music, but didn't exactly know just how to make it work. Remember, at the time he was just starting to arrange. So, I suggested that we harmonize the baritone with the trumpets and then fortify the piano and bass riffs during the mambos with the baritone. It was a hit! Today most of the orchestras now have a baritone sax. However, the people say that the baritones in those groups that utilize it don't sound like the way it does in my orchestra. That's how I came to formulate my sound.

Q: Youíve had the opportunity to experience first hand as a musician the era that most people refer to the "glory" days of this music, the Palladium days. What was that experience like for you?

A: Well that was an era that was very important to me in every aspect of my life. Musically speaking that was the very best era for this music. It was the era of the mambo. You could go downtown and from 57th Street down to 52nd Street on Broadway it was door to door clubs where this music could be heard and danced to. It was an elegant era as well. Everyone dressed well. I am a product of that era. I learned my lessons from the musicians of that era like Machito, Puente, Curbelo, Arsenio and Johnny Segui. Those were the very best orchestras of that era. It was an era of swing and nothing less. That's why I love New York so much. I love this city so much because I owe much to it for all the beautiful things I have had the pleasure of enjoying while residing here. It saddens me to see that it is no longer like that anymore.

Q: You are credited with coining the term "salsa monga". As we all know that is a term used for the period where most of the music went into a direction without swing. What is your opinion regarding that era?

A: The problem with this so-called Salsa romantica, erotica or "salsa monga" is that it was putting too much emphasis on the singers. The focus became the physical appearance of the vocalist, and not the music. The record companies are responsible for that period which we refer to as "salsa monga". It was a commercial approach aimed at the younger market. All those young singers were doing the same thing. When you bombard the market with the same thing eventually there will be a decline, and that's what is happening now. Today we are experiencing a lull in the industry as a result of that period. It wasn't so much the songs themselves, but the process of turning every ballad that had an impact in the market into a "salsa" format. Within that format the music became lame because the emphasis was on the singer. In turn the rhythm was toned down taking that edge, that swing element, away from the dancer. Today, thank God, the younger guys are realizing that this is a music that has to be played with lots of swing which in turn creates lots of excitement so that no one falls asleep. Don't forget, Machito was a singer, but his band had lots of swing. Tito Rodriguez was perceived as a singer, but his orchestra was just as swinging as any other. Don't forget he had to compete with the orchestras of Machito and Puente. In today's market the record companies have put so much emphasis on the singers that the listener doesnít even know who is playing piano, bass or percussion. Before the personnel of a band was as important as the singer. For instance, my orchestra was on a television show once back then. I had a conguero by the name of Jimmie Morales playing in the band back then. Jimmie had a recording session and could not make the television appearance so I used another conguero. After the show aired in New York I received a number of calls asking if I had fired Jimmie from the band! That is how much the public was into the personnel of a band back then. Today the personnel doesnít matter for the most part.

Q: Of all the orchestras you have had the opportunity to hear throughout you life, which one has been the most important, or the best in your opinion?

A: Tito Rodriguez's orchestra was my favorite, but I must admit that Machito's orchestra has been the single most powerful orchestra I have ever witnessed. Iíve had other favorites. I canít deny the fact that I liked the orchestras of Tito Puente, or that of Cesar Concepcion. But in retrospect when the Machito orchestra took the stand everyone listened. That for me has been the most complete orchestra of all times.

Q: When the Palladium era came to a close the scene kind of died for a period. Then along came Jerry Masucci and Fania. Jerry would eventually take the music to a new audience worldwide. What is your opinion regarding the Fania era?

A: Fania Records was the home of many excellent musicians. There were many stars involved with the label. They did not follow any patterns that may have been set along the way. They were more free to do as they felt. It was a less restricted era, a freer era that resulted in a freer sound. They were free to experiment and explore other rhythms. It was a good period for the music. Even today when they play they still manage to captivate audiences.

Q: Your orchestra has been a school for many musicians and vocalists. Vocalists like Gilberto Santa Rosa, Tony Vega, and Josue Rosado, as well as musicians like Humberto Ramirez, Piro Rodriguez, and Jimmie Morales have gone on to other great jobs from your orchestra. What do you look for in young musicians?

A: I like them to be professional. There are those that are referred to as professionals only because they are in the profession. However, to be a professional requires a lot more. One has to be responsible and of good character. You owe that to the public because they pay to see you perform. You must respect the public. When I refer to being professional I donít mean that a musician must be an excellent musician. There are excellent musicians that are irresponsible, and there are not so good musicians that are very responsible. I look for a professional musician that is responsible and able to carry out his duties. You have to remember that there is always some younger musicians looking up to you and like it or not you owe it to them to be a responsible role model to them.

Q: How do you feel about the musical scene nowadays?

A: Well, frankly I think that in Puerto Rico and New York the music is being prostituted. Anyone can sing, have an orchestra, or record. Before it wasnít like that. I had to play for four years to prove that I could play in order to just record. Nowadays they record you and then form an orchestra around you. Everything is just about making money. Itís all about trickery and deception. They sell one hundred thousand units and the company will have you believe they sold five hundred thousand units. I think the industry has completely prostituted itself in every aspect. The multi-national companies do whatever they like and the smaller fish just follow their lead. If they find a pretty face they invest lots of money then create the illusion that the artist is successful. But it is not so.

Q: How about radio? How do you feel about the situation Tite Curet Alonso is in, about the blacklisting he is facing in todayís radio markets?

A: That is a sad situation. In Puerto Rico you do not hear any of Tite Curet Alonso's music on radio. There are also other Puerto Rican composers involved in that situation. Tite just happens to be the most popular of the group. They belong to a society of composers that radio just does not want to recognize. Radio claims they want too much in royalties and just doesnít play their music to avoid paying them. Itís a sad situation especially so because the composers are always the forgotten ones. They also need to survive and make a living. It is just a sad situation for them.

Q: What can you tell us about your latest release, BACK TO THE FUTURE?

A: Well, we used that title because we were realizing that "salsa monga" was slowly dying. We were going back to the roots of this music in order to take it into the future. I believe that the future for this music lies in a balance that will satisfy the listener and the dancer equally. Itís not about El Gran Combo, Bobby Valentin, Roberto Roena, or Willie Rosario playing the music, but about whoever is playing it doing it with lots of swing, and making it exciting for the dancer, as well as for the listener. Thatís why we have to go back to the roots in order to find that certain balance. BACK TO THE FUTURE.

Q: What are your plans for the band? Will you continue touring and recording? Or will this be your farewell before retirement?

A: No! Iím still working, just taking it a little easier. You never really retire. The record company is already making plans for the next release. I want to keep playing for those people that want to dance. I want to continue doing it with timing and swing. That is what makes me happy.

Q: With that said thanks Willie and much continued success with your musical journey.

A: Thank you, and those of you who have enjoyed what I have offered.

Return to Interrogation Room

All contents © 2001 by Jazz Con Clave. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. All trademarks are property of their legal owner.